By 1908, the time was right for a new kind of agent to protect America. Above all, the new agent had to be committed intelligent ,after all the –success of any mission depends it.

The United States was, well, united, with its borders stretching from coast to coast and only two landlocked states left to officially join the union.

Inventions like the telephone, the telegraph, and the railroad had seemed to shrink its vast distances even as the country had spread west. After years of industrializing, America was wealthier than ever, too, and a new world power, thanks to its naval victory over Spain.

But there were dark clouds on the horizon.

The country’s cities had grown enormously by 1908—there were more than 100 with populations over 50,000—and understandably, crime had grown right along with them.

In these big cities, with their many overcrowded tenements filled with the poor and disillusioned and with all the ethnic tensions of an increasingly immigrant nation stirred in for good measure, tempers often flared.

Clashes between striking workers and their factory bosses were turning increasingly violent.

And though no one knew it at the time, America’s cities and towns were also fast becoming breeding grounds for a future generation of professional lawbreakers.

In Brooklyn, a nine-year-old Al Capone would soon start his life of crime. In Indianapolis, a five-year-old John Dillinger was growing up on his family farm. And in Chicago, a young child christened Lester Joseph Gillis—later to morph into the vicious killer “Baby Face” Nelson—would greet the world by year’s end.

But violence was just the tip of the criminal iceberg. Corruption was rampant nationwide—especially in local politics, with crooked political machines like Tammany Hall in full flower. Big business had its share of sleaze, too, from the shoddy, even criminal, conditions in meat packaging plants and factories (as muckrakers like Upton Sinclair had so artfully exposed) to the illegal monopolies threatening to control entire industries.

The technological revolution was contributing to crime as well. 1908 was the year that Henry Ford’s Model T first began rolling off assembly lines in Motor City, making automobiles affordable to the masses and attractive commodities for thugs and hoodlums, who would soon begin buying or stealing them to elude authorities and move about the country on violent crime sprees.

Twenty-two years later, on a dusty Texas back road, Bonnie and Clyde—“Romeo and Juliet in a Getaway Car,” as one journalist put it—would meet their end in a bullet-ridden Ford.

Just around the corner, too, was the world’s first major global war—compelling America to protect its homeland from both domestic subversion and international espionage and sabotage. America’s approach to national security, once the province of cannons and warships, would never be the same again.

Despite it all, in the year 1908 there was hardly any systematic way of enforcing the law across this now broad landscape of America. Local communities and even some states had their own police forces, but at that time they were typically poorly trained, politically appointed, and underpaid. And nationally, there were few federal criminal laws and likewise only a few thinly staffed federal agencies like the Secret Service in place to tackle national crime and security issues.

One of these issues was anarchism—an often violent offshoot of Marxism, with its revolutionary call to overthrow capitalism and bring power to the common man. Anarchists took it a step further—they wanted to do away with government entirely.

The prevailing anarchistic creed that government was oppressive and repressive, that it should be overthrown by random attacks on the ruling class (including everyone from police to priests to politicians), was preached by often articulate spokesmen and women around the world. There were plenty who latched onto the message, and by the end of the nineteenth century, several world leaders were among those who had been assassinated.

The anarchists, in a sense, were the first modern-day terrorists—banding together in small, isolated groups around the world; motivated by ideology; bent on bringing down the governments they hated. But they would, ironically, hasten into being the first force of federal agents that would later become the FBI.

The president Mckinley assassination happened at the hands of a 28-year-old Ohioan named Leon Czolgosz, who after losing his factory job and turning to the writings of anarchists like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, took a train to Buffalo, bought a revolver, and put a bullet in the stomach of a visiting President McKinley.

Eight days later, on September 14, 1901, McKinley was dead, and his vice presidentTeddy Roosevelt took the oval office.

Call it Czolgosz’s folly, because this new President was a staunch advocate of the rising “Progressive Movement.” Many progressives, including Roosevelt, believed that the federal government’s guiding hand was necessary to foster justice in an industrial society.

Roosevelt, who had no tolerance for corruption and little trust of those he called the “malefactors of great wealth,” had already cracked the whip of reform for six years as a Civil Service Commissioner in Washington (where, as he said, “we stirred things up well”) and for two years as head of the New York Police Department. He was a believer in the law and in the enforcement of that law, and it was under his reform-driven leadership that the FBI would get its start.

It all started with a short memo, dated July 26, 1908, and signed by Charles J. Bonaparte, Attorney General, describing a “regular force of special agents” available to investigate certain cases of the Department of Justice. This memo is celebrated as the official birth of the Federal Bureau of Investigation—known throughout the world today as the FBI.

The chain of events was set in motion in 1906, when Roosevelt appointed a like minded reformer named Charles Bonaparte as his second Attorney General.

The grandnephew of the infamous French emperor, Bonaparte was a noted civic reformer. He met Roosevelt in 1892 when they both spoke at a reform meeting in Baltimore. Roosevelt, then with the Commission, talked with pride about his insistence that Border Patrol applicants pass marksmanship tests, with the most accurate getting the jobs. Following him on the program, Bonaparte countered, tongue in cheek, that target shooting was not the way to get the best men. “ Roosevelt should have had the men shoot at each other, and given the jobs to the survivors.” Roosevelt soon grew to trust this short, stocky, balding man from Baltimore and appointed Bonaparte to a series of posts during his presidency.

Soon after becoming the nation’s top lawman, Bonaparte learned that his hands were largely tied in tackling the rising tide of crime and corruption. He had no squad of investigators to call his own except for one or two special agents and other investigators who carried out specific assignments on his behalf. They included a force of examiners trained as accountants who reviewed the financial transactions of the federal courts and some civil rights investigators.

By 1907, when he wanted to send an investigator out to gather the facts or to help a U.S. Attorney build a case, he was usually borrowing operatives from the Secret Service. These men were well trained, dedicated—and expensive. And they reported not to the Attorney General, but to the Chief of the Secret Service. This situation frustrated Bonaparte, who had little control over his own investigations.

Bonaparte made the problem known to Congress, which wondered why he was even renting Secret Service investigators at all when there was no specific provision in the law for it. In a complicated, political showdown with Congress, involving what lawmakers charged was Roosevelt’s grab for executive power, Congress banned the loan of Secret Service operatives to any federal department in May 1908.

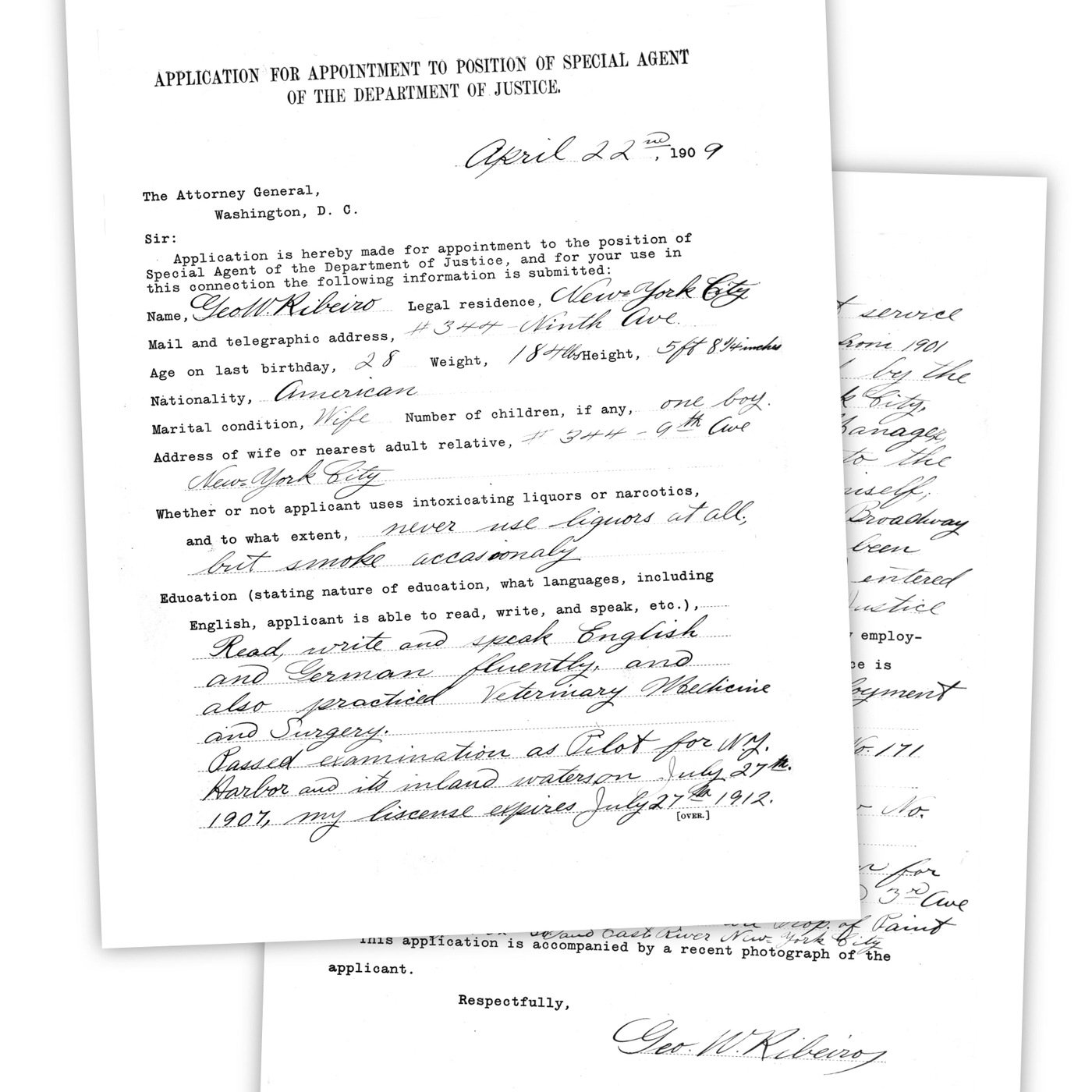

Now Bonaparte had no choice, ironically, but to create his own force of investigators, and that’s exactly what he did in the coming weeks, apparently with Roosevelt’s blessing. In late June, the Attorney General quietly hired nine of the Secret Service investigators he had borrowed before and brought them together with another 25 of his own to form a special agent force.

On July 26, 1908, Bonaparte ordered Department of Justice attorneys to refer most investigative matters to his Chief Examiner, Stanley W. Finch, for handling by one of these 34 agents. The new force had its mission—to conduct investigations for the Department of Justice—so that date is celebrated as the official birth of the FBI.

The Russian Cossack Turned Special Agent

Emilio Kosterlitzky was one of the most colorful characters to ever serve as a special agent.

A cultured, Russian-born man of the world, he spent four decades in the Russian and Mexican militaries, rising to the rank of brigadier general in Mexico. To avoid the dangerous tribulations of the ongoing Mexican Revolution, he settled down in Los Angeles in 1914.

In 1917, the same year as the Bolshevik revolution in his native land, he joined the FBI. He was 63.

Kosterlitzky was appointed a “special employee,” like today’s investigative assistant but with more authority. With his deep military experience and international flair (including strong connections throughout Mexico and the Southwest U.S. and the ability to speak, read, and write more than eight languages) he excelled at it. His work included not only translations but also undercover work.

On May 1, 1922, Kosterlitzky was appointed a Bureau special agent at a salary of six dollars a day. Because of his unique qualifications he was assigned to work border cases and to conduct liaison with various Mexican informants and officials. By all accounts, he showed exceptional diplomacy and skill.

In 1926, Kosterlitzky was ordered to report to the Bureau’s office in Phoenix but could not comply because of a serious heart condition. He resigned on September 4, 1926. Less than two years later this grand old gentleman died and was buried in Los Angeles.

The Bureau’s First Wanted Poster

On December 2, 1919, a 23-year-old soldier named William N. Bishop slipped out of the stockade at Camp A. A. Humphreys—today’s Fort Belvoir—in northern Virginia.

Shortly after Bishop’s getaway, the Military Intelligence Division of the Army requested the Bureaus’ help in finding him. One early assistant director, Frank Burke, responded by sending a letter to “All Special Agents,Special Employees and Local Officers” asking them to “make every effort” to capture Bishop.

Little did anyone know at the time, but that letter set in motion a chain of events that would forever change how the FBI and its partners fight crime.

In the letter, Burke included every scrap of information that would help law enforcement of the day locate and identify Bishop: a complete physical description, down to the pigmented mole near his right armpit; possible addresses he might visit, including his sister’s home in New York; and a “photostat” of a recent portrait taken at “Howard’s studio” on seventh street in Washington, D.C.

Burke labeled that document—dated December 15, 1919—“Identification Order No. 1.” In essence, it was the Bureau’s first wanted poster, and it put the organization squarely in the fugitive-catching business just eleven years into its history. It has been at it ever since.

Within a few years, the identification order—or what soon became known throughout law enforcement as an “IO”—had become a staple of crime fighting. By the late 1920s, these wanted flyers were circulating not only throughout the U.S. but also Canada and Europe (and later worldwide).

The IO evolved into a standard 8×8 size, and the Bureau soon added to them fingerprints (thanks to its growing national repository), criminalrecords, and other backgroundinformation. By the 1930s, IOs were sent to police stations around the nation, enlisting the eyes of the public in the search for fugitives. In 1950, building on the “wanted posters” concept, the FBI created its “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list.

And what of Mr. Bishop? With the help of the identification order, he was captured less than five months later, on April 6, 1920.

With Congress raising no objections to this new unnamed force as it returned from its summer vacation, Bonaparte kept a hold on its work for the next seven months before stepping down with his retiring president in early March 1909.

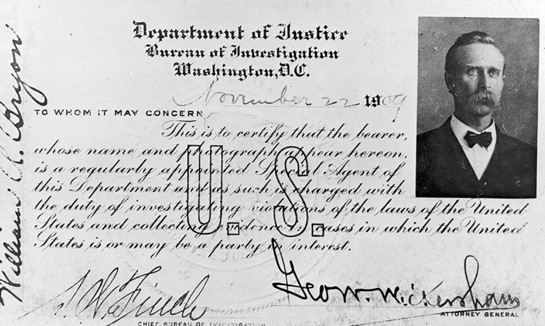

A few days later, on March 16, Bonaparte’s successor, Attorney General George W. Wickersham, gave this band of agents their first name—the Bureau of Investigation. It stuck.

During its first 15 years, the Bureau was a shadow of its future self. It was not yet strong enough to withstand the sometimes corrupting influence of patronage politics on hiring, promotions, and transfers.

New agents received limited training and were sometimes undisciplined and poorly managed. The story is told, for example, of a Philadelphia agent who was for years allowed to split time between doing his job and tending his cranberry bog. Later, a more demanding J. Edgar Hoover reportedly made him chose between the two.

Still, the groundwork for the future was being laid. Some excellent investigators and administrators were hired (like the Russian-born Emilio Kosterlitzky), providing a stable corps of talent. And the young Bureau was getting its feet wet in all kinds of investigative areas—not just in law enforcement disciplines, but also in the national security and intelligence arenas.

At first, agents investigated mostly white-collar and civil rights cases, including antitrust,land fraud, banking fraud, naturalization and copyright violations, and peonage (forced labor).

It handled a few national security issues as well, including treason and some anarchist activity. This list of responsibilities continued to grow as Congress warmed to this new investigative force as a way to advance its national agenda. In 1910, for example, the Bureau took the investigative lead on the newly passed Mann Act or “White Slave Traffic Act,” an early attempt to halt interstate prostitution and human trafficking.

By 1915, Congress had increased Bureau personnel more than tenfold, from its original 34 to about 360 special agents and support personnel.

And it wasn’t long before international issues took center stage, giving the Bureau its first real taste of national security work. On the border with Mexico, the Bureau had already opened several offices to investigate smuggling and neutrality violations. Then came the war in Europe in 1914. America watched from afar, hoping to avoid entangling alliances and thinking that 4,000 miles worth of ocean was protection enough. But when German subs started openly sinking American ships and German saboteurs began planting bombs on U.S. ships and targeting munitionsplants on U.S. soil, the nation was provoked into the conflict.

Congress declared war on April 6, 1917, but at that point its own laws were hardly up to the task of protecting the U.S. from subversion and sabotage. So it quickly passed the Espionage Act and later the Sabotage Act and gave responsibility to the principal national investigative agency—the Bureau of Investigation—putting the agency in the counter-spy business less than a decade into its history. The Bureau also landed the job of rounding up army deserters and policing millions of “enemy aliens”—Germans in the U.S. who were not American citizens—as well as of enforcing a variety of other war-related crimes.

The war would end in November 1918, but it was hardly the end of globally-inspired turmoil within the U.S. The Bolsheviks had taken over Russia in 1917, and Americans soon became nervous about its talk of worldwide revolution, especially in the face of its own widespread labor and economic unrest. A wave of intolerance and even injustice spread across the nation not only against communists but also against other radicals like the “Wobblies,” a sometimes violent labor union group called the Industrial Workers of the World. When anarchists launched a series of bombing attacks on national leaders in 1919 and 1920, a full-blown “Red Scare” was on.

One of the first special agents credentials.

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer responded with a massive investigation, led by a young Justice Department lawyer named J. Edgar Hoover, who amassed detailed information and intelligence on radicals and their activities. The ensuing “Palmer Raids” were poorly planned and executed and heavily criticized for infringing on the civil liberties of the thousands of people swept up in the raids. The incident provided an important lesson for the young Bureau, and its excesses helped temper the country’s attitudes toward radicalism.

A new era of lawlessness, though, was just beginning, and the nation would soon need its new federal investigative agency more than ever.

per fbi.gov